García Márquez, the copywriter.

About that time when Gabo made it big in advertising and lost it all for writing his most celebrated novel. Plus: Audioflux in Washington.

Hola!

It’s been a while since we last connected. Between life and the news, I’ve been feeling a bit overwhelmed, so I took some time to think about a story that would be pleasant to read, share, and talk about.

In a year where we are all asking a robot to write for us, I’ve been thinking a lot about creativity (and more specifically, writing) as a craft. It’s strange: we know how crucial and precise it is to tell something well, but precisely because of the effort it requires, we ask a machine to do it for us.

And it doesn’t. And we try again. And again. That’s what it feels like to ask a robot to write for you. We criticize AI for killing creativity. But I think the debate should be somewhere else.

We’re confusing high-volume content publishing with creativity.

We consume fast. That’s why in recent years we’ve conflated creating with producing, and started thinking of it as an unlimited resource.

But true creativity isn’t just doing for the sake of doing. It means bringing something original into the world.

And that, my friends, takes more than a good prompt.

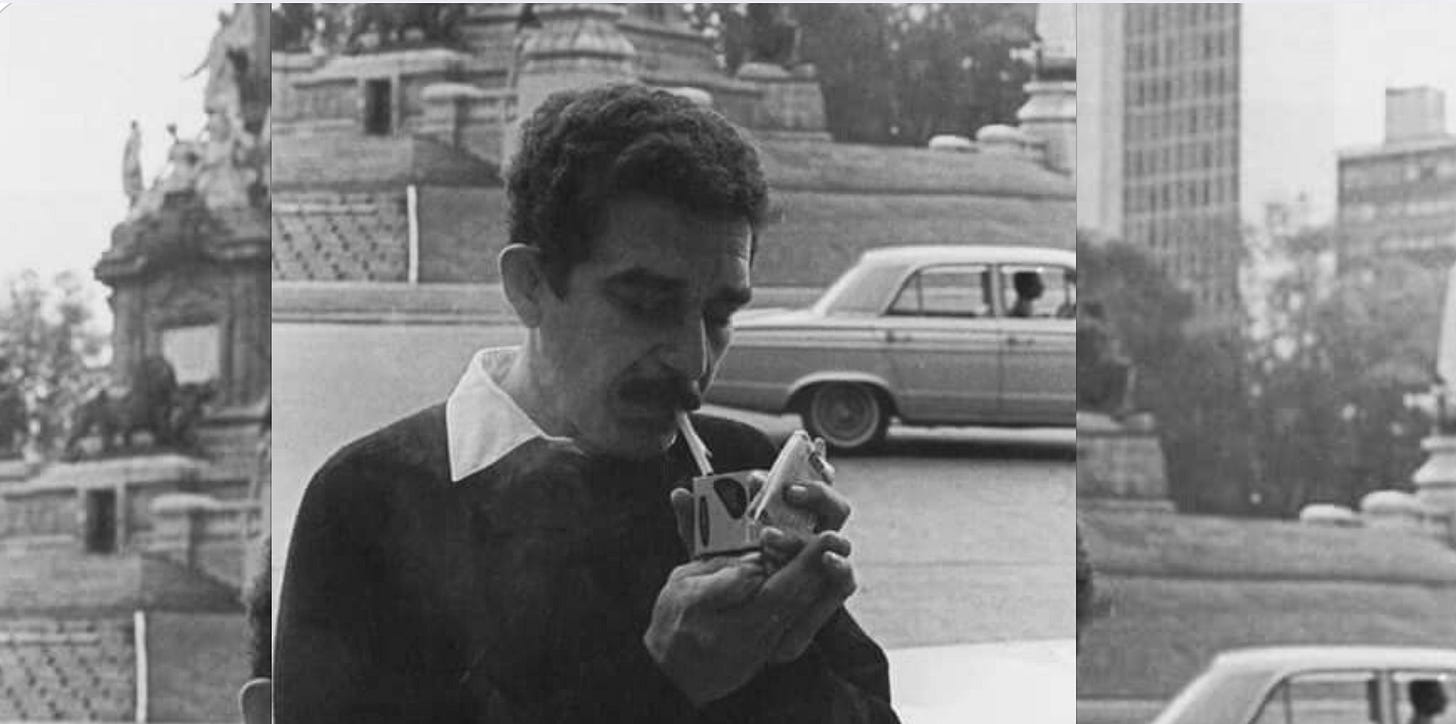

That’s why I’m dedicating today’s edition to Gabriel García Márquez at 34 years old, with his black curls and thick mustache, looking out over Mexico City from the fourth floor of a business tower.

A quick announcement, and then we’ll dive into the story.

Anyone in Washington?

Julie Shapiro and John DeLore brought me on board as one of the producers for the upcoming Audio Flux Circuit 5. It has been the most heartwarming project of my year so far. Audioflux is a little haven of experimental audio that unfolds in editions, like a fanzine or magazine. The new circuit was inspired by vintage 3D photographs. For one day only, all the pieces will premiere at the garden of the Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum 💛 I’ll be there. 💛 If you know anyone in DC, spread the word—we want to meet more audio lovers.

Ahora sí.

Gabo and Mercedes arrived in Mexico City one early morning in 1961. They came from the north, on a train, after traveling for days on a Greyhound bus from New York to the border. He had just finished a stint as a reporter for Prensa Latina. He wanted to leave journalism behind to devote himself to filmmaking. In those days, Julio Jaramillo sang on the radio, "I want to buy five cents’ worth of happiness from life."

At the station, the poet Álvaro Mutis was waiting for the couple.

It’s strange to imagine them getting off that train, carrying their life in their suitcases. Even more so to remember that at that moment, Gabo was 34 years old and as broke as any young immigrant in any era.

They rented a small apartment with Mercedes in the same tower where Mutis lived. It was near the bar district and close to downtown. After the first few months of getting by however they could, the screenwriting gigs took longer than expected, the films didn’t come through, and Gabo had to lean on friendship for support. That’s how he ended up working as a copywriter in an ad agency.

“From the fourth floor of a building on Melchor Ocampo Street, number 135—where the agency was located—Gabriel García Márquez looked out the window toward Roma. At the time, the Circuito Interior highway didn’t exist, and you could see the square framed by Paseo de la Reforma with its balustrades on both sides and the trees at the entrance to Chapultepec Forest.”

—Raúl Renán, poet and Gabo’s colleague at the agency (1992).

Gabo, the copywriter

His colleague Raúl Renán recalls that the Nobel laureate didn’t enjoy being stuck in his cubicle—he preferred to roam the company’s hallways or stare out the window with a coffee in hand. Writing copy, for him, was more of a leisure game, and he was always chatting with someone. Still, he kept regular office hours and delivered on creative briefs with slogans like “Pan para pan Bimbo” (Bread for Bimbo bread).

At night, he wrote short stories at full gallop on his typewriter. Renán says they were all poor and lived in mediocre mid-range apartments. At that time, Mercedes was pregnant. According to Centro Gabo, “they slept on a mattress on the floor, and all their furniture consisted of a small table and two chairs.” García remained close to the literary scene and expanded his circle of friends, something that would prove very important a couple of years later.

That’s what his thirties were like: a writer by night, a copywriter by day—too much of a poet for advertising.

Eulalio Ferrer (advertising executive) says that Gabo also had his missteps. Like a campaign for Kodak, where the slogan he wrote was:

“This could be the last Christmas of your life. Preserve your image in the memory of your loved ones with the new Kodak Instamatic.”

I don’t know why, but it brings me a bit of comfort to think of a literary legend going into an office. I’m sure no one asks who the copywriter was when they see a commercial, but writing is always more than just the words. That’s why, when Jorge Cardoze, former agency director, retired, he said the campaign he remembered most was one written by Gabo:

“Calmex, señora, Calmex.”

Mercedes had to be very patient, for sure, after giving birth. The Nobel laureate wrote for tuna brands, banks, airlines, and cigarette companies. He didn’t win any home appliances in the end-of-year raffles, didn’t get a raise or a promotion, but he never stopped writing.

“One day he left me speechless when he sat down in the only visitor’s chair I had in my office and, without any preamble, launched into the story of an old angel who is discovered, fallen in the backyard of a house, by its inhabitants—a couple well past middle age who are suddenly faced with an extraordinary situation.” (Renán, 1992.)

Referring to what would later become the short story “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.”

And then it came Cien Años de Soledad.

By 1965, Gabo and Mercedes were financially stable, so much so that they moved into a spacious house in a quiet neighborhood. They had another baby and remodeled the house to welcome guests. García told his friends that the children were happy to have space to run around all day, and he had set up a paper-filled room to write in. “I was writing like a train,” he said in an interview. On the radio, perhaps “Cuando calienta el sol aquí en la playa” was playing.

Life might have continued that way if not for Acapulco.

“Suddenly, at the beginning of 1965, I was heading to Acapulco with Mercedes and our two children for the weekend when I was struck by a cataclysm of the soul so intense and shattering that I barely managed to avoid hitting a cow that had wandered onto the road.”

—Gabriel García Márquez, “One Hundred Years of Solitude: The Novel Behind the Novel”

Gabo had the revelation: that he needed to tell a story in the tone his grandmother used. And that’s how One Hundred Years of Solitude was born.

Some sources say he quit the agency, others say he was fired for being a poor copywriter. What’s certain is that from that weekend on, he left the stability of a fixed salary behind to pursue the mission of writing a novel for the next 18 months.

It’s known that they sold the car to get some cash, which only covered the first three months. As the months went by, Mercedes received help and food from their many writer friends. I refuse to call the path García chose “heroic” because the truth is it meant extreme hardship for him and his family. A published writer is not a demigod, and the job of a copywriter is no less creative.

Why is it that when a struggle involves an artist, it gets romanticized?

What sane person would choose to lock themselves away among piles of paper to write a novel instead of enjoying a life of luxury and prosperity?

I ask you because I don’t have the answers. The only thing I know is that in his interviews, Gabo would say writing was the loneliest profession in the world, just as he also said that the only thing he cared about in life was being a good writer.

So tell me:

Do we create art despite scarcity, or out of stubbornness, to prove that art is a way to make a living?

When Gabo finished writing those 700 pages, they didn’t have the 82 pesos needed to mail the manuscript to the publisher. They had half, and that’s what they sent. They went back home, gathered the last three appliances they had, Mercedes took them to the pawn shop, and came back with the money.

Then they sent the second half of the novel and walked away with 21 pesos. As they left the post office, Mercedes, furious, told him:

—The only thing left now is for the novel to be bad.

When the first edition of One Hundred Years of Solitude was published, the acknowledgments on the opening page were dedicated to Jomi García Ascot and María Luisa Elio. Jomi was the one who had given him his first job at the ad agency.

I’m sorry, but I don’t really care if AI is yapping.

What I care about is whether the creator economy will solve the problem of having to choose between being an artist and living in precariousness

I care about how we keep ourselves from pawning things like Gabo did, in an era where publishing and distribution seem free, but actually cost us the currency of our own enthusiasm.

Tell me if the use of robots solves the everyday tasks—doing the dishes, taking out the trash, and tidying the house—so we can have the time to bring something original into the world.

Ask your bosses not to defund friendship.

Each subscription to this space supports my research and writings like this one 💛. If you'd like to support me, subscribe.

Today’s edition comes with a bibliography:

Jáuregui, I. (2023, 18 de enero). El viaje a Acapulco que inspiró Cien años de soledad. Travesías Digital. https://www.travesiasdigital.com/destinos/mexico/sur/guerrero/acapulco/el-viaje-a-acapulco-que-inspiro-cien-anos-de-soledad/

Martínez, G. A. (2023, 16 de mayo). Se alquilan escritores (microhistorias de la publicidad mexicana). Confabulario, El Universal. https://confabulario.eluniversal.com.mx/se-alquilan-escritores-microhistorias-de-la-publicidad-mexicana-2/

Centro Gabo. (2023). La vida de Gabriel García Márquez en la Ciudad de México. https://centrogabo.org/gabo/contemos-gabo/la-vida-de-gabriel-garcia-marquez-en-la-ciudad-de-mexico

Mendoza, M. L. (2023). Gabo ardía como llamarada de fe. Milenio. https://www.milenio.com/cultura/gabo-ardia-llamarada-fe-china-mendoza

Abdala, V. (2023). Salen a la luz cartas inéditas de Gabriel García Márquez: “No seré otro escritor de corbata”. Clarín. https://www.clarin.com/cultura/salen-luz-cartas-ineditas-gabriel-garcia-marquez-escritor-corbata_0_Su8u4MYPF.html

Cultura Colectiva. (2023). Las frases publicitarias de Gabriel García Márquez que seguro no conocías. https://culturacolectiva.com/arte/letras/las-frases-publicitarias-de-gabriel-garcia-marquez/

Ruleta Rusa. (2023). Yo sin Gabo no puedo vivir. https://www.ruletarusa.mx/historiasrr/yo-sin-gabo-no-puedo-vivir/

Milenio. (2023). Renán 21. https://www.milenio.com/cultura/renan-21

BBC Mundo. (2017, 12 de enero). Gabriel García Márquez: 5 cosas que quizás no sabías del autor de Cien años de soledad. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-38588005

La Historia del Día Blog. (2017, 5 de mayo). Gabriel García Márquez: Cien años de soledad, la novela detrás de la novela. Publicado originalmente en la Revista Cambio.

Milenio. (2023). María Luisa Elío: la voz de alguien. https://www.milenio.com/cultura/laberinto/maria-luisa-elio-la-voz-de-alguien

Genial esta historia, Laura! Como todo lo que haces…

Qué maravilla :)